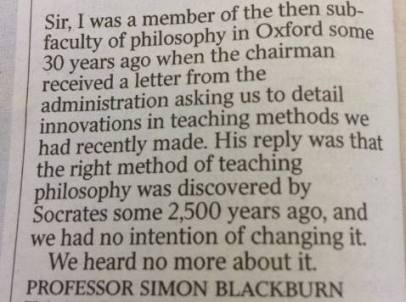

Consider the following letter to the editor from the well-known philosopher Simon Blackburn:

“Sir, I was a member of the then sub-faculty of philosophy in Oxford some 30 years ago when the chairman received a letter from the administration asking us to detail innovations in teaching methods we had recently made. His reply was that the right method of teaching philosophy was discovered by Socrates some 2,500 years ago, and we had no intention of changing it. We heard no more about it.” Professor Simon Blackburn

In reply to Blackburn’s chairman, I’m tempted to say: “How very un-Socratic of you!” But that’s too cute (even for this blog) and I’d probably be wrong anyway—in Plato’s dialogues at least, Socrates does indeed recommend his own method(s). My criticism of the chairman’s claim is more nuanced. I begin by showing that at least two distinct teaching methods can be and have been attributed to Socrates. Then I show that both methods, when taken literally, have their own distinctive shortcomings. My aim, however, is not to show that we, as teachers, should reject Socratic teaching, but rather that we utilize his teaching methods critically, with an awareness of their own problematic assumptions and potentially negative consequences. This too is Socratic.

WHAT IS THE SOCRATIC METHOD?

This question itself is problematic, since Socrates employs more than one teaching method. Consider this encounter between Socrates and a couple of his “students.”

Socrates comes across two well-respected generals, Laches and Nicias. Naturally, he asks both about what it means to have courage. Initially, Laches confidently defines courage in the following way: “if someone is willing to stay in ranks and ward off the enemy and not flee, rest assured he is courageous.” Socrates, however, remembers something about the 479 B.C. battle of Plataea: “[T]hey say that the Spartans at Plataea, when they met troops using wicker shields, refused to stand and fight but fled, and when the Persians broke ranks, the Spartans [wheeled around] to fight like cavalry and so won the battle.” Laches is forced to rethink his original definition of courage. So he tries this: Courage is “a kind of perseverance of soul.” In other words, courage is a kind of endurance. Again, Socrates raises a problem with this definition: perseverance can be directed toward impulsive and foolish ends. Nicias, with the judicious guidance of Socrates, “comes to the rescue” by proposing that courage would have to involve knowledge not only of what things to fear and to be confident about, but also an awareness of good and evil, and could not always be limited to warfare. Socrates thus takes an initial definition of a concept and subjects it to criticism, trying to come to some knowledge about its meaning.

This encounter is typical of Socrates; however, what he is ultimately doing here can been interpreted differently. In other words, when it comes to his teaching style, at least two distinct methods are regularly attributed to Socrates. Let’s call one the Critical Thinking approach and the other the Truth Seeking approach.

C r i t i c a l T h i n k i n g

Here’s a typical expression of the Critical Thinking approach: “The oldest, and still the most powerful, teaching tactic for fostering critical thinking is Socratic teaching. In Socratic teaching we focus on giving students questions, not answers. We model an inquiring, probing mind by continually probing into the subject with questions” (Foundation for Critical Thinking). There is no pre-determined argument or end-point to which the teacher attempts to lead the students. “Teachers” and “students” are seen almost as peers, engaged in the same pursuit of answers. The only essential difference between “teachers” and “students” is that the former has probed longer and has experienced that certain paths of inquiry are more promising than others. It’s easy to see Socrates in this light. For Socrates insisted many times that he was not a “teacher,” at least in the traditional sense of spoon-feeding knowledge to those who lack the knowledge themselves. In practical terms, this means no textbooks, no lectures, no Powerpoints, no exams, minimal note-taking, if any, and small classes.

T r u t h S e e k i n g

Socrates engages in questioning others and himself in a search for truth. As demonstrated in his conversation with Laches and Nicias, he challenges the assumptions of their views by asking continual questions until a fallacy or contradiction is exposed. His aim, however, is far from destructive or subversive; one can easily see this conversation as part of a larger dialectic whose aim is to uncover the truth or at minimum get closer to it, however long this may take. Possible answers to what courage is are eliminated—including those offered by Laches and Nicias—thus narrowing the search for the meaning of courage. Let me explain.

Socrates is concerned with the knowledge of concepts such as courage, justice, and beauty. Since there is no recognized procedure or accepted method for coming to such knowledge, Socrates has to argue for his own method. In Plato’s dialogue Meno, Socrates does just that, by arguing that the answers to these questions are to be found within our souls. In fact, the word “education” comes from the verb “to educe,” to draw forth from within. Socrates’ method here is therefore specifically geared to help us retrieve these answers from within. It is then not surprising that he sometimes calls himself a “midwife of ideas.” Now, these answers are called definitions. A true definition is one that accurately describes the essence or nature of the thing to be defined; it is objectively true. For example, the true definition of courage captures the essence of courage. It doesn’t matter whether or not people agree or disagree with that definition. Its truth doesn’t depend on what we think or believe, or even if no one was ever courageous. Imagine Cowardly Earth, where no human ever shows courage in anything they do and no one has ever thought about courage. Nonetheless, courage possesses an eternal and unchangeable essence.

The Critical Thinking and Truth Seeking approaches, as described above, are certainly distinct from one another. Both teaching methods have their virtues, but only when taken in moderation. Here’s why.

CRITIQUE

When taken to its extreme, the Critical Thinking approach to teaching faces two problems. First, it can engender a “question everything” attitude, especially in beginning students. Even “Philosophy Talk,” an otherwise fantastic podcast out of Stanford University, introduces each show with the mantra: “The program that questions everything except your intelligence.” This attitude can easily be taken too far, and even the podcasters Ken Taylor and John Perry have no patience for those who question the value of equality, respect for others, and the like. But what if we question the very enterprise of questioning? Isn’t this the logical endpoint of the Critical Thinking approach? In other words, the Socratic Method (taken as immoderate critical thinking) carries the seeds of its own destruction. I observed a class once where I saw the spirit of inquiry die over the course of the semester, precisely because inquiry itself was questioned and was found pointless and wanting. The teacher and a single persistent student were helpless in resuscitating the others.

Second, using the critical thinking approach to teaching can engender complacency and even laziness in the teacher and ultimately frustration in the student. Consider what some have said about law school (at least American ones) in a well-known blog: “The Socratic method as a cruel game designed to let professors show off how clever they are while students struggle to tease out basic concepts from boring cases is well-established. It was the basic dispute between the Harvard casebook approach and the ‘shut the hell up and take notes’ approach that raged almost two hundred years ago.” Continuing, “The Socratic method is the method used by sage law professors to tease the law’s nuances out of the minds of their brilliant pupils. In practice, it leads to lazy law professors with little real world experience calling on whichever gunner feels like talking that day…. The classes consist of meandering discussions that often have no real point and leave students even more confused than before” (Above the Law). As you can imagine, this can be incredibly frustrating for students. I daresay that law school isn’t the only place where such complacency and frustration occur.

Socrates’ Truth Seeking approach, on the other hand, faces its own problems, for it makes two contentious assumptions. First, it assumes that there is a true definition (essence) of concepts such as courage, justice, and beauty to be discovered. But Ludwig Wittgenstein argues in his 1953 Philosophical Investigations that things which are believed to share one or more essential common features may actually be connected by a series of overlapping similarities, where no one feature is shared by all. Wittgenstein uses games to illustrate this idea.

“Consider for example,” Wittgenstein says in §66, “the proceedings that we call ‘games’ [e.g., card games, board games, ball games, and Olympic games] to look and see whether there is anything common to all.” “We can go through the many, many other groups of games in the same way; we can see how similarities crop up and disappear.” We want to say, “there must be something common among games, but we’d be wrong. “The result of this examination is: we see a complicated network of similarities overlapping and criss-crossing: sometimes overall similarities.” Wittgenstein concludes by stating: “I can think of no better expression to characterize these similarities than family resemblances.”

If examples of courageous acts are analogous to games in the sense that they too share no one essential feature in common—and when you see philosophers in action, it sure seems that they are analogous to games—then the Truth Seeking paradigm of Socratic inquiry faces a deep, perhaps fatal, problem.

Second, even if concepts such as courage have an essence (that is, the set of essential properties that all acts of courage share in common), whatever that essence is has been stripped of any capacity to mold itself to the circumstances, to change with the times, for it is the product of abstraction from concrete courageous things. Socrates himself realized that courage’s essence would have to be an abstract thing, or as he puts it, a permanent, changeless, and timeless Form or Idea. Nietzsche calls such abstractions “concept-mummies” in Twilight of the Idols:

You ask me which of the philosopher’ traits are really idiosyncrasies? For example, their lack of historical sense, their hatred of the very idea of becoming, their Egypticism. They think that they show their respect for a subject when they de-historicize it, when they universalize it… when they turn it into a mummy. All that philosophers have handled for thousands of years have been concept-mummies; nothing real escaped their grasp alive…. Death, change, old age, as well as procreation and growth, are to their minds objections—even refutations.

Never mind that Nietzsche tends to exaggerate; he has a point. Socrates, Plato, and a veritable treasure-trove of philosophers, de-contextualize concepts, as if the definition of courage is permanent, changeless, and timeless. But acts of courage themselves are not at all abstract; they are concrete, contextual to both circumstance and time, and varied.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Don’t get me wrong. I often employ the Socratic Method(s) in my classes. But I take both varieties—critical thinking and truth seeking—in moderation. As teachers, we don’t need to re-debate the morality of slavery, any more than geologists need to re-debate the shape of the earth. Neither do we need to take concepts such as courage to have essences; we can treat them as open concepts. We can continue to think critically and to seek the truth.